A Beautiful Facebook Group Is Reclaiming History. As It Grows, Can It Stay Beautiful?

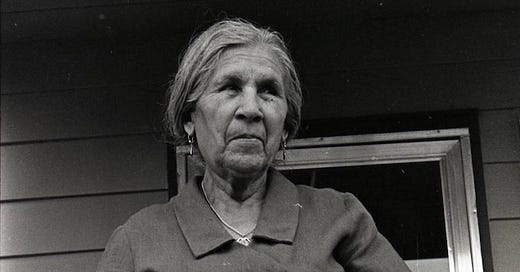

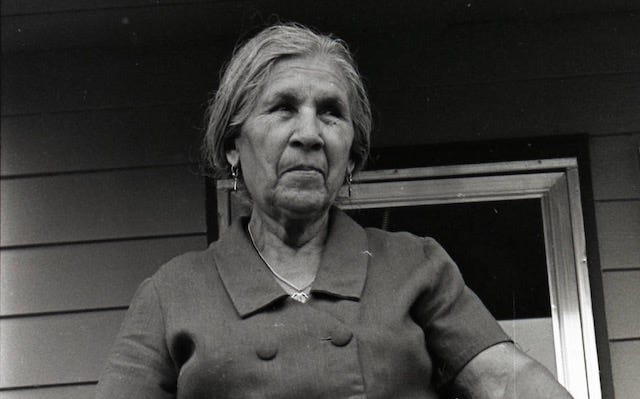

In the archive, she was catalogued as “Woman standing on porch.” But she had a name, and it surfaced last month in an unusual Facebook group devoted to adding life to thousands of still images sitting in a scarcely known collection in rural Washington State. Most of the images being examined by the Facebook group are nearly 50 years old, taken by Seattle photographer Irwin Nash after he set out to chronicle the experience of Latino farmworkers in the Yakima Valley during a pivotal period in their struggle for greater rights.

The Facebook group’s small clan of idealistic detectives, amateur oral historians, and thrilled descendants of farmworkers offers quite a contrast to the usual news coming out of Facebook’s much-criticized “groups” feature in recent years. Once touted by Mark Zuckerberg as a way to “strengthen the social fabric,” Facebook groups have instead been used to spread hate, promote dangerous falsehoods, drive radicalization, and hatch destructive plots like the one aimed at kidnapping Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer. According to an internal Facebook report, groups on the platform also “helped incite the Capitol insurrection.” And according to researchers, Facebook’s algorithm for nudging people into groups has for years pushed users toward extreme content. That problem apparently led Facebook to temporarily shut off its group recommendation engine in the weeks before the last presidential election, a step that unfortunately wasn’t enough.

Then there’s the Nash Photo Collection Facebook group, where beautiful tributes and names keep coming in for the individuals in the long-forgotten photographs. If the primary words Facebook’s critics associate with its groups right now are “polarization,” “misinformation,” and “violence,” here is a relatively unknown Facebook group dedicated to producing their opposites, adding new layers of rich humanity and personal truth to a topic long viewed through lenses clouded by racism, acrimony, and misunderstanding. As the group’s members work, they’re also building awareness of an obscure archive that, for most of its life, has been loved mainly by archivists.

The group was created in April after the archive of around 9,300 photographs, all housed at Washington State University in Pullman, south of Spokane, received a sudden push toward full digitization. That surprise push came about due to a remarkable collision of pandemic-era odysseys undertaken by separate individuals working in different hushed libraries on opposite sides of the state.

The consequences of their colliding journeys have been manifold, and they include a loving tribute shared with the Facebook group a few weeks ago that named the “Woman standing on porch.” It was from a person who identified himself as her son.

“Martina Molina Gamboa is standing on the porch of her house in Outlook, Washington in 1971,” the tribute read. “She was one of thousands of Mexican immigrants who migrated to the Yakima Valley in the late 1940s-1970s from Texas and other states to work the sugar beet, asparagus, potato, mint, and hop fields, and the apple, cherry, [and] pear orchards.” The tribute describes how Gamboa grew up in Mexico “during the turbulent years of the Mexican Civil War” and later migrated to the Rio Grande Valley in Texas, where she was a domestic worker.

Eventually, it explains, “the Gamboa family migrated to the Yakima Valley and began working in the fields where they were paid by piece rate, according to how much they produced. At that time, agricultural workers were excluded from all labor legislation in this state and had no coverage under minimum wage, unemployment insurance, child labor, or health and safety laws. In order to make ends meet, the four oldest girls were pulled out of school and began working full time in the fields. Dorotea, the youngest, was only 12 years old when she became a full time farmworker.”

Even when housed in worker camps that lacked running water or indoor toilets, Martina Molina Gamboa kept her family well-fed with homemade tortillas and well-clothed with polished shoes for school. “In 1970, when the farmworkers movement started in the Yakima Valley,” the tribute says, “Martina opened her home to the organizers who came [from] out of town to help.” Those activists included Irwin Nash, the Seattle photographer who took her picture on the porch, and Cesar Chavez, whom Nash captured in a number of photos in the archive, including this one:

Seattle attorney Laura Solis had never heard of Irwin Nash when she and her partner Mike Fong, a deputy mayor in Seattle, began reviewing images of old newspapers stored on microfiche at the University of Washington’s Suzzallo Library. Microfiche isn’t everyone’s kind of fun, but it’s their kind of fun and the couple were happy to devote their weekends to using it in an attempt at unraveling a particular Solis family mystery. She grew up among farmworkers in the Yakima Valley and had been working in recent years on an ancestry project. In conversation with her father one day, he’d told her that her uncle once ended up in a local newspaper photograph with a high-level Nixon Administration official whom Solis assumed must have come to the Yakima Valley because of worker unrest. Solis’s mother thought the year of the photograph might have been 1971. So Solis and Fong set out to find the photo, which led them to the Suzzallo Library microfiche.

“In the process of doing that we were actually reading the stories,” Solis recalled, “and it turns out, not coincidentally, that this was a time when there were conversations being had about farmworkers, and the needs of farmworkers, and the housing conditions for farmworkers.” Solis noticed, however, that the local newspaper stories from the time generally left out the voices of actual farmworkers. “It was just so stark,” she said. “Just seeing this play out in microfiche… It made me sad. Some of the stories were just outright racist.”

Solis and Fong didn’t find the photograph they were searching for but were determined to keep looking. Then COVID hit. The pandemic made them reluctant to spend more time in the library, so Fong began hunting for resources online and sending links to Solis. “And that’s when I saw the Washington State University link,” she recalled. The link led her to about 100 digitized photographs from the Irwin Nash archive that had been posted on a hard-to-find web page a decade ago.

Those photos, scanned by a graduate student who happened to take an interest in them, offered just a small sampling of the thousands of Nash prints, negatives, and contact sheets that have been stored for nearly half a century in hermetically sealed, temperature-controlled spaces in WSU’s Manuscripts, Archives, & Special Collections division. Viewable only with special permission, the full set of images was originally purchased from Nash in the 1990s and handed over to WSU during a meetup in a motel room. Given the volume of photographs, Nash was able to provide only scant information about the people in his pictures.

“At first I didn’t really know what I was looking at,” Solis said of the 100 digitized images. She guessed she might have landed in some sort of newspaper archive, but as she started paging through the photographs she realized there were no articles, just pictures of people, many of them working in asparagus fields. “It was so surreal to see this, because I felt like I was being transported back to the time when I did that work with my family,” she said. “I just kept feeling: I know these people.”

What Solis had stumbled into was a visual record of the lives left out of those one-sided newspaper narratives she’d found so upsetting and unfair. “This is the missing piece,” she thought. “This is the thing that nobody talked about.”

Growing up, Solis often felt invisible. Yet here in this remote online stash of 100 photographs was “this visual depiction of people—the people that I came from. The kind of work that my parents did that wasn’t depicted in news stories and wasn’t really talked about in the community… And they were done in such a beautiful way that really showed their perspective. It was almost like seeing into a mirror. Seeing your own experience, through someone else’s eyes, but you recognize it.”

One photograph in particular captured Solis’s attention. In it, a woman identified as “mother Elizondo” was harvesting asparagus and storing the fresh stalks in a large box affixed to her hip. There were Elizondos in Solis’s extended family. So she posted the photograph to Facebook to see what her relatives might say. Her aunts commented immediately, talking about the memories the image brought back. Then, a few days later, her cousin posted a tribute on his Facebook page that identified the woman as his grandmother (meaning the woman was Solis’s grandaunt).

“Because of her I know why family matters,” Solis’s cousin wrote. “Because of her I am who I am. Because of her I live with humility and respect for those who showed me the way and endlessly sacrificed for their families. Because of her I will always value the little things in life that she worked so hard for every early morning and long hot day. I love you Grandma Elisa Elizondo and thank you for showing me the way.”

At that moment, Solis thought: “This is really much bigger than just our family.’”

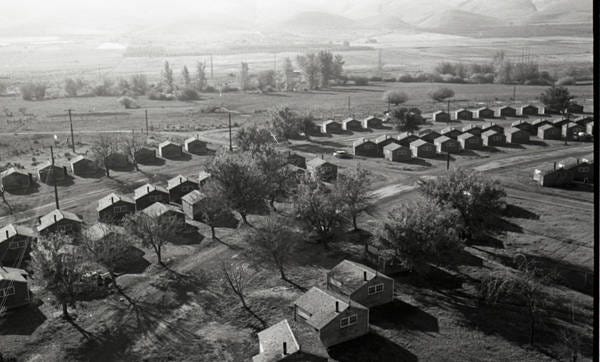

At Washington State University, the manager of the school’s Kimble Digitization Center, Dr. Lipi Turner-Rahman, had also been thinking the Nash collection could be destined for something bigger. She’d heard of an $8,000 grant being offered by the Washington State Libraries to fund a worthy digitization project and had begun looking through WSU’s various special collections, wondering which one of them might make a the best candidate. Then COVID hit and she had a lot more time to think. She decided the Nash collection was the one because it contained “a nice, finite number” of images to digitize, and also because the grant was intended to benefit the people of Washington State. WSU is a land-grant institution, Dr. Turner-Rahman explained, “and our purview is to make lives better for the citizens of Washington.” She believed this digitization project could “help the Yakima valley community reevaluate their sense of themselves and their history.”

As Dr. Turner-Rahman worked on the grant application, the university’s archivist mentioned to her that he’d recently heard from a man named Mike Fong who seemed very interested in the Nash collection. That led Dr. Turner-Rahman to the Seattle couple whose search in the University of Washington microfiche archives had, eventually, brought Solis to that online backwater of a web page holding 100 Nash images.

Fong and Solis were enthusiastic about the grant possibility, and Fong helped generate letters of support for the application. The Nash archive ended up getting the grant, but $8,000 wasn’t enough to digitize the entire collection. So connections were made with local Seattle groups interested in supporting this drive to daylight the history of Latino farmworkers, and from those connections an additional $13,000 was raised.

Suddenly, after decades of having to limit access to the collection, Dr. Turner-Rahman could see a clear path to digitizing the entire Nash archive by the middle of this year, a milestone that would allow all the photos to be placed online, where anyone with an internet connection could view them. She decided she shouldn’t stop there.

“I felt, as a person of color myself, that we couldn’t really just stop with digitizing the material,” Dr. Turner-Rahman said. “That it was really important to have names of the people and stories of the people in the photographs, because it really is about putting their counter-stories out there. Because there is a narrative in the US about, you know, that this is a white country and people came, they made it great, this stuff. And we tend not to look at other communities and their achievements, what they gave to the story. And that’s what I’m looking for. In my work, I want to showcase that—those counter-stories of people who get ignored.”

She thought about using Facebook to solicit the counter-stories. She also thought about sending people into the Yakima Valley community to collect in-person oral histories from those whose memories might enhance the public’s understanding of moments captured in Nash’s photographs. But for the time being, these were only thoughts.

In March, having caught wind of the digitization grant from Fong and Solis, Sandeep Kaushik, a political consultant and former full-time journalist, wrote an engrossing longform article exploring the “nearly forgotten” Nash archive, Solis’s discovery of the Elisa Elizondo photo, and the window the archive now offers onto what one activist called “the awakening of a people.”

Kaushik published his article at Post Alley, a small online media outlet whose readership tends toward Seattle’s civic employees and professional do-gooders. Compared to the norm for articles posted on the site, Kaushik’s piece received a large amount of attention. But in a reminder of how fragmented the media environment has become, it wasn’t until the Yakima Herald newspaper picked up the ball and ran a front-page feature showing a number of Nash collection photographs that Dr. Turner-Rahman really began hearing from people in the Yakima Valley. They knew the individuals in those images. They wanted to share their stories.

In its way, the Yakima Valley reaction was also a reminder that old media still does some things better than new media. The Yakima Herald published its article on April 18, in “a medium that a large portion of that community are reading,” Dr. Turner-Rahman noted, and “that morning I had people email me: ‘This is my sister. This is my brother.’”

It was this experience that pushed her to forge ahead with the idea of a Facebook group, which she’d been discussing with Fong and Solis. “And it really took off,” Dr. Turner-Rahman said.

By Facebook standards, the Nash Photo Collection group, with just under 300 members, is not large. But by Facebook standards it seems exceptionally inspiring, and likely because of that, it’s growing. With this increasing scale come familiar and challenging questions about the potential downsides to the vast reach and immediate impulse gratification Facebook offers its users.

“When I started the Facebook group, I was a little nervous, I will not lie,” Dr. Turner-Rahman said. She’s well aware of how Facebook groups have been used for ill in recent years. Solis, too, worries the group could grow large enough to attract the kind of people who dedicate significant amounts of their time to befouling the internet: trolls, mean-spirited meddlers, anti-immigrant racists. That’s been the arc of countless online endeavors that, like the Facebook groups idea itself, began by showing fantastic promise for enriching the human experience but ended up being overtaken by digital waves of contempt, scorn, dehumanization, lying, deranged attention-seeking, and all sorts of other destructive impulses that seem to be emboldened in the virtual realm.

Some of the Nash photos themselves, Solis noted, document tension between the white power structure in the Yakima Valley and activist farmworkers. “It’s not like that tension has necessarily gone away over the last 50 years,” she said. “It’s something you sense in the community today. I think that potentially it’s a powder keg.”

But for now, Dr. Turner-Rahman and Solis are amazed by what’s happened in the group up to this point. Neither of them can think of anything quite like it. The Nash Photo Collection Facebook group is a crowd-sourced historical excavation. It’s an ad hoc narrative reclamation. It’s an exercise in making and deepening intergenerational connections. It’s mystery-solving done digitally. It’s just plain exciting. And the tone of the discourse, so far, has one of respect, awe, and celebration.

To protect this great vibe, the group is open only to people who are either invited or ask to be let in and are willing to answer one or two straightforward questions.

“Facebook is just another tool,” Dr. Turner-Rahman explained. Because of its massive scale and well-developed tagging, photo-sharing, and commenting features, it happens to be a perfect tool for this project. But it’s not the only useful tool for gathering names and oral histories that fill out the stories the Nash photographs begin to tell. People still call and email Dr. Turner-Rahman directly with new information, and those people tend to be older than the ones engaged in the Facebook group.

At the moment, Dr. Turner-Rahman feels comfortable with the veracity of the facts being surfaced by the group because it still has a manageable number of members, allowing her to see familial connections between people and get a sense of how each person would know what they claim to know. “But if I opened it up to the whole wide world, it would be a totally different kettle of fish,” she said. “I think it works if it’s in a small environment. I think scale is the issue.”

To Solis, another thing going for the Nash Photo Collection Facebook group is that it’s a virtual project tied to a distinct physical space, the Yakima Valley. “Yeah, it’s online, and it’s virtual, but you know these folks,” she said. “Or you know people who know them, and they’re related to you. And I think that may help… It’s their families. It’s their lives.”

In a way, the rare and wonderful dynamic in this Facebook group supports an idea floated at a recent US Senate hearing on how digital platforms are shaping public discussion and individual minds. Dr. Joan Donovan of Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government used the hearing to call on the US government to give digital platforms new “public interest obligations.” As Dr. Donovan explained it, such obligations would force companies like Facebook to “curate timely, local, relevant, and accurate information.” In other words, a government mandated, all-of-company effort to essentially encourage the positive atmosphere, fact-finding orientation, and local focus of the Nash Photo Collection group across the rest of Facebook.

For his article at Post Alley, Kaushik ended up tracking down Irwin Nash. Initially, he’d assumed the photographer was dead but in fact he is very much alive, “84 years old and… currently living in an assisted living facility in Seattle,” as Kaushik reported.

Nash “grew up in Seattle’s Central District, the son of Jewish immigrants from Poland who emigrated in the 1920s hoping both to escape anti-Semitism and to improve their economic circumstances,” Kaushik wrote. “His upbringing in Seattle led to his burgeoning political activism and concern for the plight of the downtrodden, which eventually took him to the Yakima Valley’s agricultural fields in 1967 and kept bringing him back through the mid-70s.”

Of the work he did there, Nash told Kaushik: “This was a labor of love. It needed to be done.”

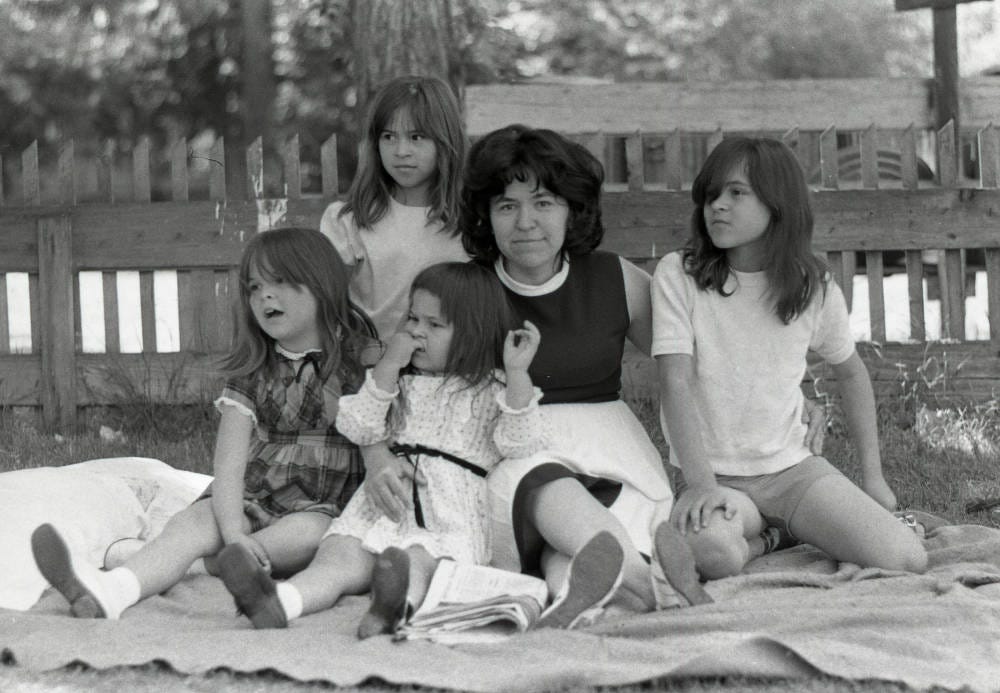

Newly digitized images are now being regularly added to the online archive of Nash collection photographs. That, in turn, feeds progress in the Facebook group. Last week, Dr. Turner-Rahman shared a post with the group showing a digitized image of a family sitting on a blanket in a grassy field. “I love this photo of a young family,” she wrote. “I would love to give names to all the members of this family. Let us know if you know them.”

In the comments, someone noted that there is another photo in the Nash collection of this same family, apparently in the same field and on the same blanket, holding a United Farmworkers Flag. “That might imply something more active,” the person wrote, posting the second image.

“Good catch!” Dr. Turner-Rahman responded.

The next comment came from Angela Ann Treviño: “Oh my goodness!! That's me and my mom [and] sisters.”

“Which one are you?” Dr. Turner-Rahman commented back.

Treviño, who now has the image with the UFW flag set as her Facebook picture, replied: “I am on the left holding corner of flag..looking at my mom...I remember this day. I miss my mom ..she was my hero !!”

Some of the stories I’ve been reading this week:

• “Amazon is the retailer” — In California, an important court ruling about who’s to blame when a product sold on Amazon ends up being harmful.

• “How Jeff Bezos Beat the Tabloids” — A fast and fascinating read, excerpted from a forthcoming book.

• While the US waits, the world regulates — “Tech giants are facing increasingly hostile foreign governments that are taxing their profits, attempting to halt their acquisitions, labeling them as monopolies and passing laws to limit their powers,” Axios reports. Meanwhile: “The U.S. is still struggling to figure out what it wants to do.”

• Plus lots of takes on the Facebook Oversight Board’s decision about Trump, including this one:

Questions? Tips? Comments? wildwestnewsletter@gmail.com