Facebook Subpoenaed My Reporting Records. With Help from Substack, I Pushed Back.

Now that Facebook has lost its trial court fight against Washington State’s “gold standard” political ad transparency law, I’m free to tell a side-story to this twisty legal drama. It’s the story of how I got served with a subpoena from Facebook last winter seeking nearly four years of my reporting records. It’s also a story of gratitude to Substack and its Defender program, which paid for a great lawyer who helped me push back against the $430 billion company’s attorneys and kept me from having to turn over anything. I hope this story serves as an example of why it’s so important that platforms like Substack and organizations like the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press offer legal support to local journalists when they face costly intrusions on their rights.

It was November 2021 when I was served with Facebook’s subpoena. At that point, I’d been writing about Facebook’s failure to comply with Washington State’s unique political ad disclosure law since December 2017, first at The Stranger and then here on Substack. None of that reporting made me the kind of money one needs to hire fancy lawyers for a fight whose end is uncertain.

Facebook’s subpoena “commanded” that I sit for a deposition and turn over “ALL DOCUMENTS” sought by the company’s lawyers concerning a time period from December 2017 to the present. The subpoena’s definition of “DOCUMENTS” included, but was not limited to, “any and all COMMUNICATIONS.” So I was to turn over any documents and communications, from 2017 to the present, if they related to a long list of things outlined in the subpoena. (And “RELATED TO,” the subpoena explained, meant “concerning, referring to, describing, evidencing, interpreting, reflecting...”) In short, here is the list of subjects for which I was to turn over related documents and communications:

Facebook political ads targeting Washington State.

Facebook’s failure to disclose required information about those political ads.

Complaints I’d filed with the Washington State Public Disclosure Commission after Facebook repeatedly failed to provide me with information that “any person” is entitled to have about local political ads targeting Washington State’s elections. (Those PDC complaints happen to be publicly available online.)

Communications between myself and “any other person or entity” regarding Facebook or Washington State’s disclosure law.

Communications between myself and five people I’d either mentioned by name or quoted on the record in stories I’d published on this issue over the past several years:

Laura Edelson, a computer scientist at New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering (who, a few months before Facebook subpoenaed me, had very publicly accused Facebook of trying to stifle her research into the company's political ads and misinformation issues).

Shannon McGregor, a senior researcher with the Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Travis Ridout, the Thomas S. Foley Distinguished Professor of Government and Public Policy at Washington State University.

Tallman Trask, at the time a Seattle law student and activist who’d also filed complaints about Facebook’s failure to disclose details on political ads.

Zachary Wurtz, a person who defies easy description and was the main character in one of my most popular Substack stories: “The Guy Who Beat Facebook in Small Claims Court.”

Plus, for good measure, “anyone acting on their behalf.”

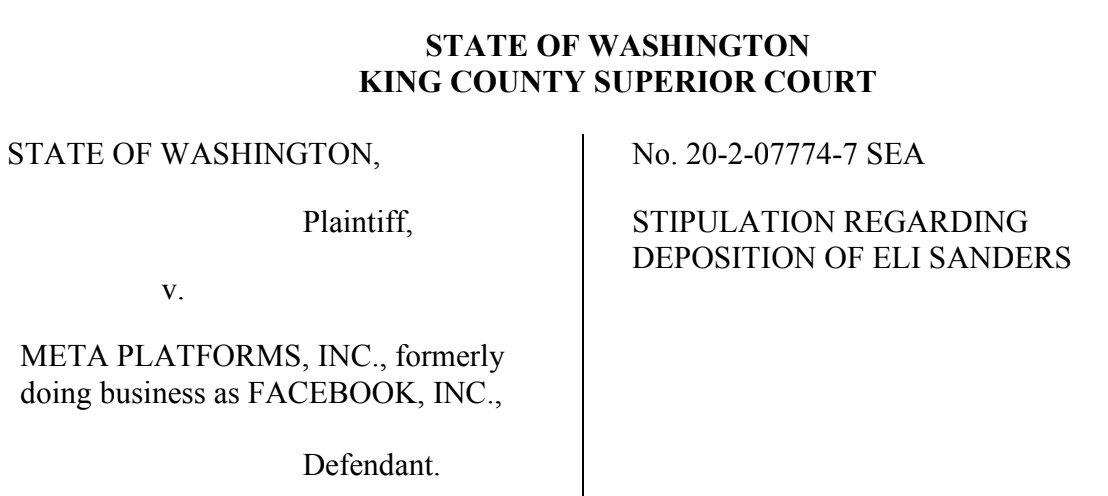

Here’s an image of that section of the subpoena:

I knew, reading the subpoena, that I needed a lawyer. In my past work at media companies there was always a lawyer available, on the company’s dime, to handle such things. Not in the independent journalism world. I reached out to the Substack Defender program, which offers help in such situations and was a major reason I’d felt comfortable publishing on this platform in the first place. Just in case, I also reached out to the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and its “Protecting Journalists Pro Bono Program.”

Within days, the Substack Defender program had come through for me and I was being represented, on Substack’s dime, by Michele Earl-Hubbard, a First Amendment lawyer in Seattle who’s an expert on Washington State public records laws and the Washington State reporters’ shield law.

The subpoena I’d received was signed by Rob McKenna, a former Republican attorney general for Washington State now working as a local attorney for Facebook. (McKenna also used to be a semi-regular panelist with me on KUOW’s week-in-review program. Small world!) Interestingly, both McKenna and my new attorney, Earl-Hubbard, had been proponents of Washington State’s shield law for journalists. After being enacted in 2007, the measure created a high bar for subpoenaing reporters’ records. When lobbying for the shield law as attorney general, McKenna once said in a press release: “I believe that the reporter’s privilege is important to maintaining an open and accountable government and society.” Hey, me too!

As the lawyers got into it, Facebook explained that it had decided to subpoena me because I’d been listed by the State of Washington as a trial witness in the state’s case against Facebook. This was true. In November 2020, about a year before Facebook’s subpoena arrived, the state told me I was a witness to Facebook’s then-alleged failure to comply with state disclosure law.

At the time, I hadn’t thought much of it. From where I sat, it seemed obvious that I’d witnessed a failure to comply with the law, and I figured that if the state’s lawsuit ever went to trial—in the end, it didn’t; Judge Douglass North ruled against Facebook at the summary judgment stage—then maybe I’d be called on to say: Yes, I requested that Facebook give me data about political ads as required by Washington State law; no, Facebook did not give me all the data required by the law; and yes, I then filed complaints with the Washington State Public Disclosure Commission.

I saw my PDC complaints as being in line with other journalistic efforts to enforce sunshine laws for the benefit of the public good, and I saw potentially describing my complaints in court as right in line with what NYU journalism professor Jay Rosen describes as the essential “pro-democracy” function of the press. I also had memories, from my early days as a journalist, of covering criminal trials in King County Superior Court and seeing other journalists from local outlets stand up to argue, off the cuff, for having cameras in the courtroom during certain proceedings. That, too, left me with the impression that part of a journalist’s job is to make sure open government laws are working as intended, if necessary by speaking in court.

What I could not understand was why Facebook, to prove its (ultimately failed) argument that Washington’s disclosure law can’t withstand constitutional and legal scrutiny, would need to dig through years of my reporting records. More baffling was what Facebook even thought it might find. As anyone reading my published, publicly available stories could see, my reporting wasn’t based on leaked documents, company secrets, or even anonymous sources. It was more about the absence of records—records Facebook wouldn’t give me, even though Washington State law requires them to be handed over to “any person” who asks.

I later realized that the academics Facebook mentioned in the subpoena, the ones who’d been quoted or mentioned in my past articles, had all ended up acting as expert witnesses for the state in its lawsuit against Facebook. But that still didn’t resolve my bafflement as to why Facebook needed records of my journalistic interactions with those academics in order to prove that Washington’s disclosure law was, as Facebook unsuccessfully alleged, unconstitutional.

Whatever Facebook’s motivations, the principle I sought to defend was clear: No rummaging through my reporting notes and communications. My stories were out there for Facebook to read. The work behind those stories was off limits, in order to protect people’s trust that confidential statements to journalists will stay confidential and not be pried into the public realm at some later date by subpoena.

Ultimately, Facebook’s long list of demanded documents went away. With the help of Earl-Hubbard’s excellent lawyering and Substack’s money, a “stipulation” was eventually filed with King County Superior Court. In that stipulation, both the state and McKenna, signing on behalf of Facebook, agreed that I would sit for a deposition with very narrow parameters. They also agreed that Facebook, by that point calling itself Meta, would withdraw its document subpoena after my deposition. Under the terms of the stipulation, the deposition could not be an inquiry into my sources. It was not a waiver of my shield law rights. And the topics were basically what I described above: my requests to Facebook for political ad data that the company was required to disclose; Facebook’s response (or non-response); and my complaints to the PDC.

McKenna and the state signed that stipulation on April 12 of this year. A couple weeks later, I skipped my constitutional law class (with a plan to watch it later on Zoom recording) and sat for a relatively brief deposition. After that, as I understood it, there was no more document subpoena and this particular adventure was over—unless the case went to a full trial.

Since Judge North’s ruling last week assures this case is not going to a full trial, I can now share my brief journey in subpoena-resisting. I share it with deep gratitude for Substack’s readiness to fight on my behalf, and with additional gratitude for Earl-Hubbard’s quick work and the solid advice and support I received from the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press along the way. Without that kind of backup, this might have been a very different story. Having had what I consider to be a good outcome, I can now only hope that more independent journalists get these sorts of resources and outcomes when they need them.