"Participatory Disinformation"

Back in March, I wrote about a presentation I couldn’t shake. It came during the unveiling of “The Long Fuse,” a report by academics and other digital experts who set out to understand the mechanics behind the waves of online misinformation that roiled the 2020 election.

One way of generating that election misinformation stuck out. At the time, researchers who worked on the “Long Fuse” described it as the “bottom up” dynamic, and they seemed to be at a loss for how it could be addressed. The “bottom up” dynamic is essentially locally-grown misinformation that’s created when random Americans misinterpret events around them, often because they’ve been primed by big-name politicians and partisan media to see plots against them everywhere.

These genuine misunderstandings by real people inevitably get posted to social media. When they do, they’re then carried up an online influencer food chain to powerful partisan voices who opportunistically amplify and validate the false beliefs expressed in the postings (because doing so offers some perceived partisan benefit). During the 2020 election, Exhibit A for this “bottom up” dynamic was “Sharpie-gate.”

“Sharpie-gate” began with real confusion among voters in Arizona. Like all Americans, these voters had been warned repeatedly by former President Donald Trump and others that a “rigged” election was coming. On alert for vote-tampering, these wary Arizonans noticed that certain pens provided at certain polling places were bleeding through ballots. This was neither a problem for accurate ballot-counting nor an anti-Trump conspiracy. But it was cast as both, especially after conservative online influencers got hold of the Arizonans’ misinformed social media postings. This, in turn, made “Sharpie-gate” into a sizable scandal that reinforced the distrust and grievance that had generated the false reports of Sharpie-connected funny business in the first place.

I got flashbacks to “Sharpie-gate” and the “bottom up” dynamic when I read a recent Twitter thread from Kate Starbird, one of the academic researchers who contributed to “The Long Fuse” report. Starbird is a professor affiliated with the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public, and in her Twitter thread she used a new term to describe the “bottom up” dynamic. Or, at least, a term that was new to me.

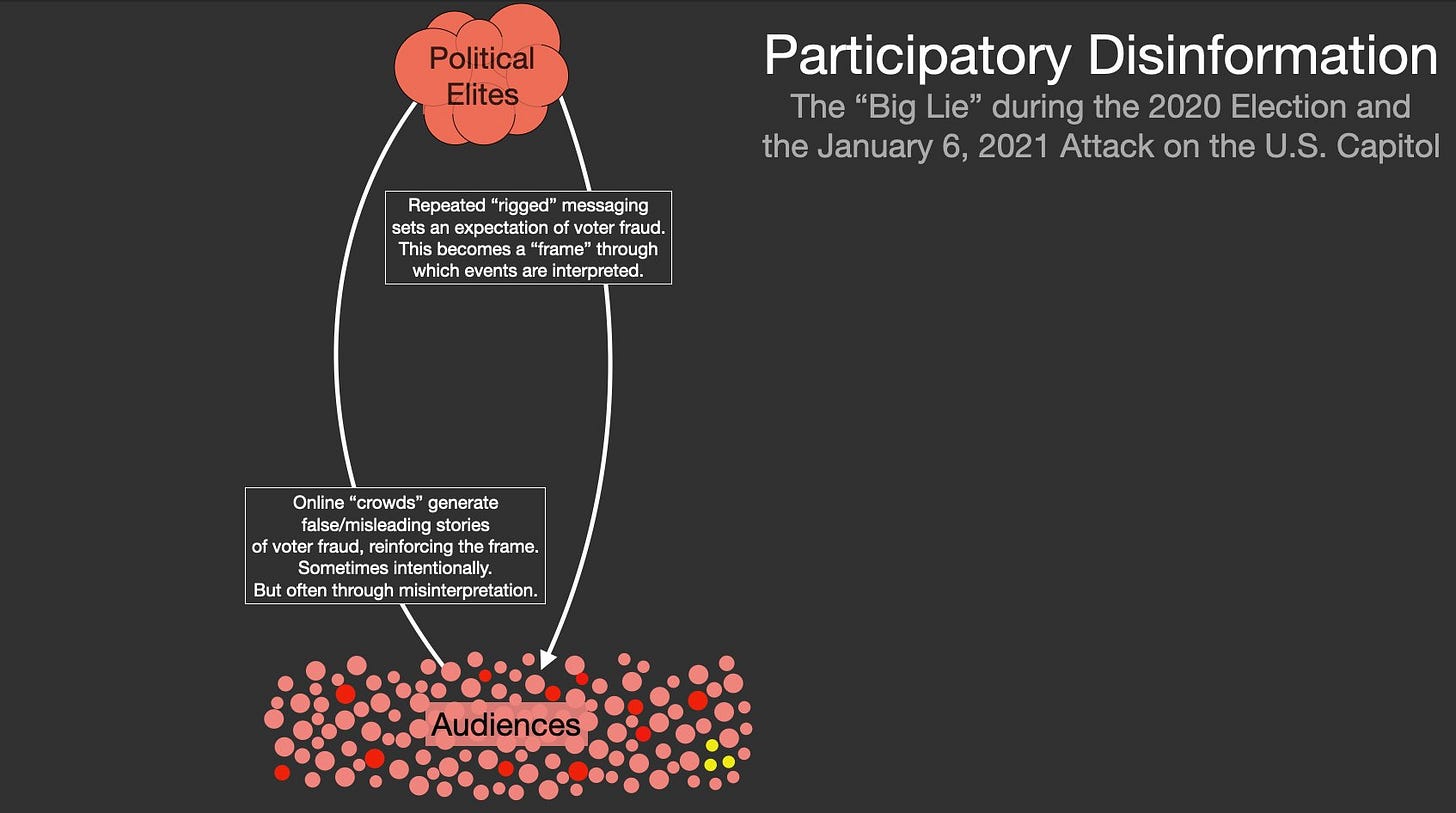

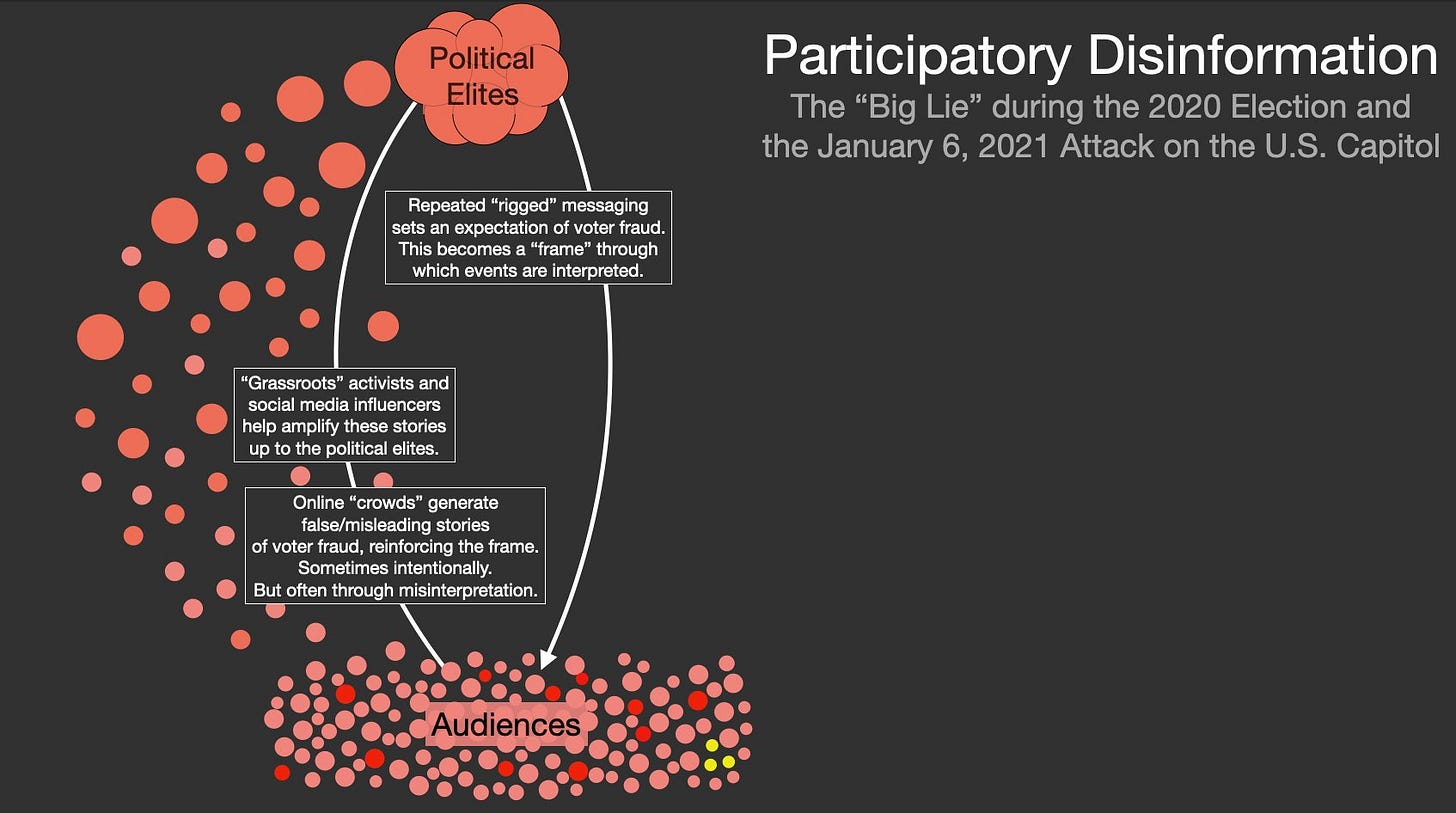

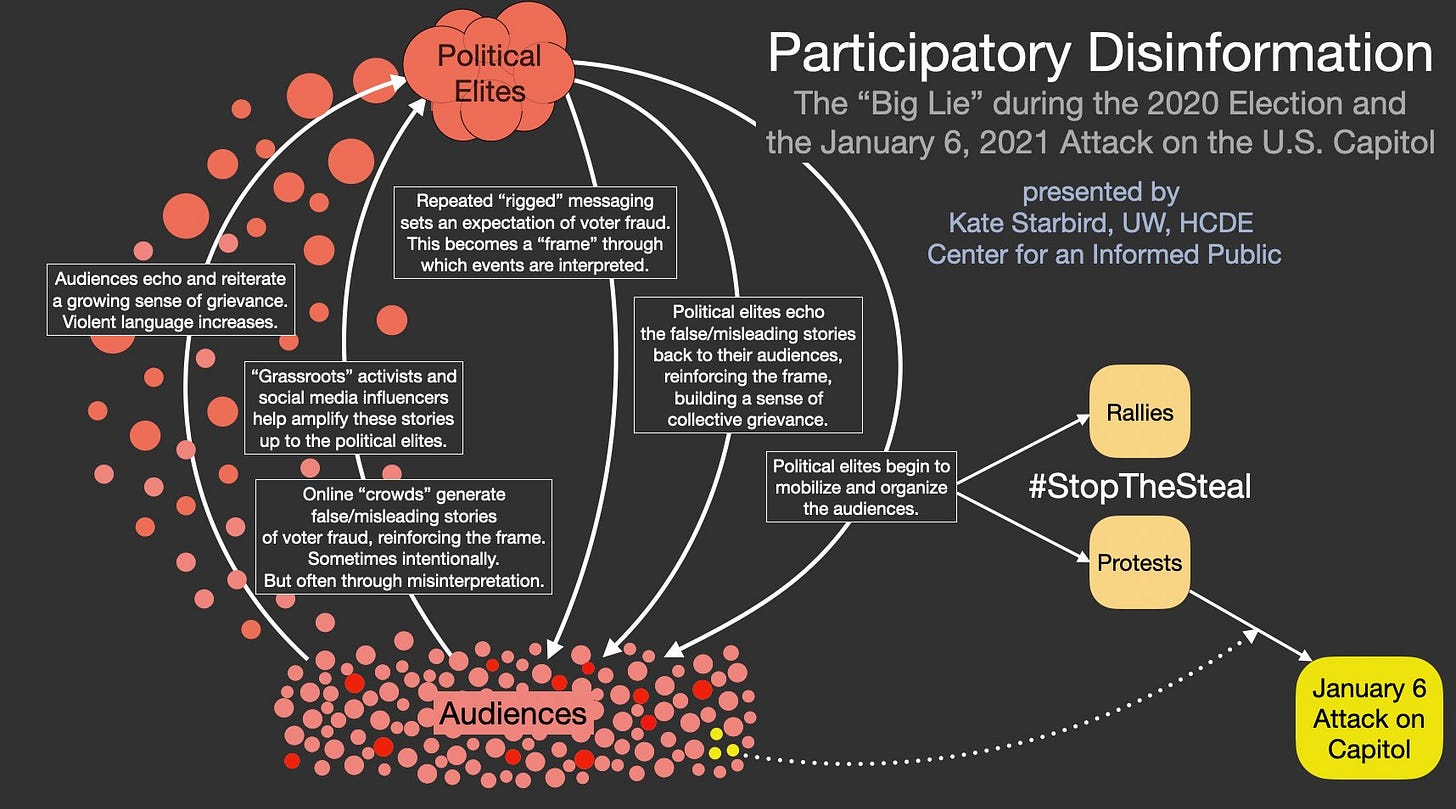

“Participatory disinformation” is what Starbird calls it now. It’s a nomenclature that offers a dark echo to the better known idea of “participatory democracy” (an idea that, at least in theory, undergirds the entire American experiment). Not only does Starbird offer an arresting new name in “participatory disinformation,” she also offers companion charts to show how it works.

At a time when top Republicans like Liz Cheney are still required to embrace the “Big Lie” about a stolen election or face expulsion from the leadership ranks, and as related lies about supposedly rampant voter fraud in American elections get used to justify a flurry of new Republican-backed proposals for harsh voting restrictions, Starbird’s charts are worth looking at. The Center for an Informed Public has kindly given me permission to share a number of them here.

“Let’s start from the beginning,” Starbird wrote on Twitter. “We have ‘elites,’ including elected political leaders, political pundits and partisan media outlets, as well as social media influencers who have used disinformation and other tactics to gain reputation and grow large audiences online… We also have their audiences — the social media users and cable news watchers who tune into — and engage with — their content.”

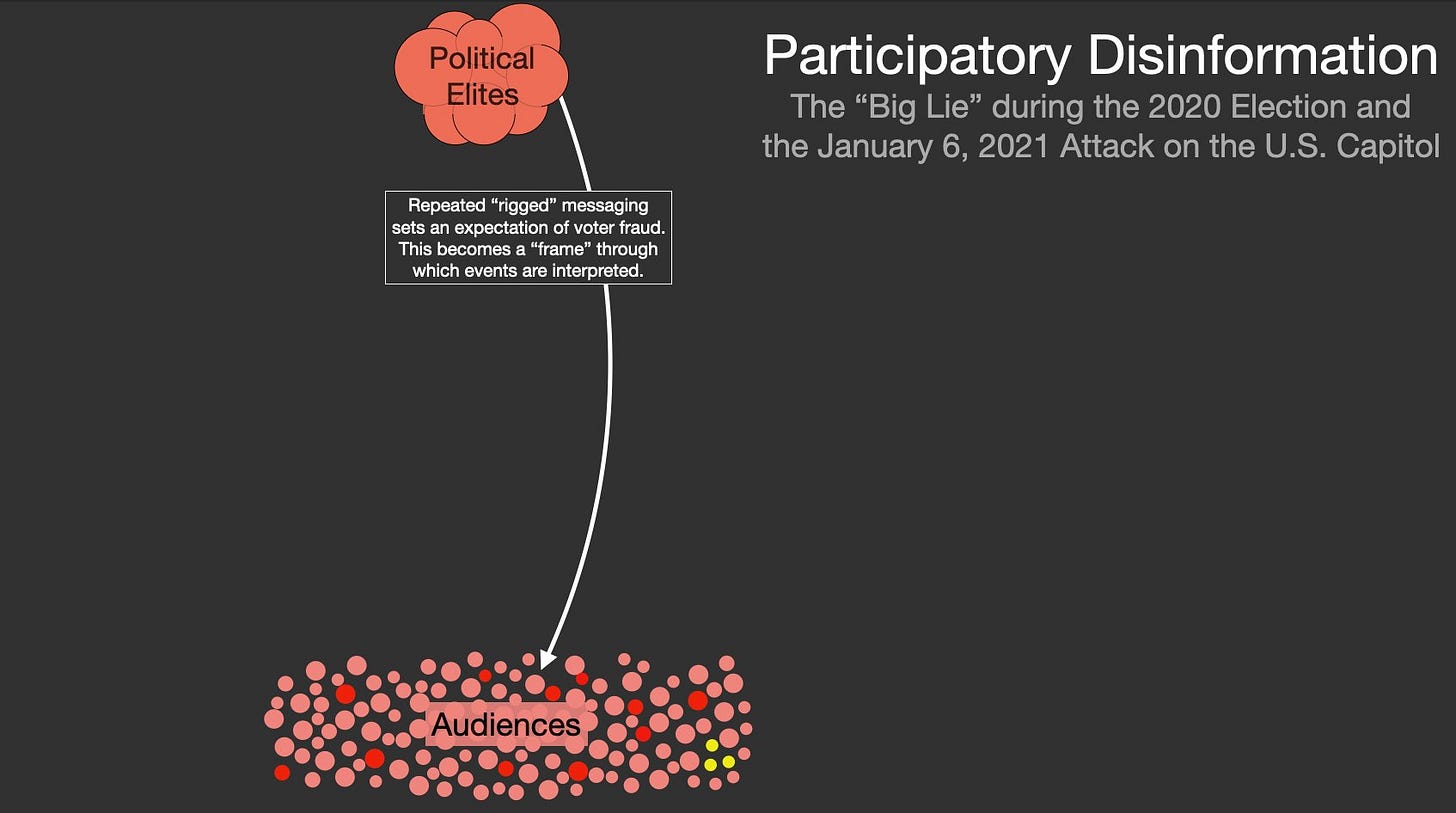

First, Starbird explains, the elites send warnings down to their audiences. In the case of the “Big Lie,” it was warnings from Trump and others about massive voter fraud leading to that “rigged election.”

The online audiences, thus primed, begin to see evidence of rigging everywhere, including in the form of Sharpie pens. This, in turn, leads to crowd-crafted narratives that fit the foregone confusion of a stolen election. Next, partisan social media influencers help these false ground-level narratives rise.

Policital elites then echo those false narratives back down to their audiences. That stirs the audiences up even further, solidifying their fury and sense of victimhood. “Violent language and calls to action increase,” Starbird wrote on Twitter. And then, seeking to move things offline, the elites figure out various ways to channel this rage into real life actions.

Rallies are organized. Hashtags are floated. Protests are staged. In the case of the #StopTheSteal campaign, which was birthed in part by this dynamic, the terminus is, as we now know, an attack on the US Capitol as the not-actually-rigged election is being certified.

Seeing this dynamic charted out feels uniquely clarifying. It also shows that while technologically novel, this online “participatory disinformation” dynamic is, fundamentally, a digital twist on a very old form of propaganda. Starbird’s final graphic, evocative of a retro radio tower icon, turned my mind toward the radio station that propelled the Rwandan genocide. That station achieved its aims by nurturing hate in its audience until the audience was echoing sufficient hate back and showing its readiness to be channeled toward violent action.

Writing in The Atlantic in 2019, Kennedy Ndahiro offered an oblique warning to then-Trump-led America about such incitements while also drawing a line back from the Rwandan radio station’s strategies to earlier Nazi strategies:

It was Joseph Goebbels who said, “That propaganda is good which leads to success, and that is bad which fails to achieve the desired result. It is not propaganda’s task to be intelligent; its task is to lead to success.”

We are out of the Trump administration, if not the Trump era. But we are still stumbling through a disorienting moment of ascendant digital platforms, greatly diminished numbers of fact-oriented journalists, and declining trust not only in the news media but also in other institutions that help separate lies from truth in our democracy.

How does a society in the midst of such a moment break the circuit on factually wrong, malevolently seeded, Goebbels-style “good” propaganda? How do we reckon with the large number of very online Americans who seem either easy marks for this new “participatory disinformation” or, worse, gleeful enlistees?

I still don’t think anyone has the answers. But it’s at least something, for now, to see the problem charted out by Starbird in such a clear way.

Some of the stories I’ve been reading this week:

• Biden’s secret Venmo — It’s not so secret if you know where to look (as Buzzfeed did). That highlights “a privacy nightmare for everyone.”

• “The Deadly Toll of Amazon’s Trucking Boom” — A grim, important investigation by The Information.

• Attorneys General try to halt Instagram for kids — “Facebook has historically failed to protect the welfare of children on its platforms,” write 44 attorneys general in a letter trying to stop the creation of a child-focused Instagram. “The attorneys general have an interest in protecting our youngest citizens, and Facebook's plans to create a platform where kids under the age of 13 are encouraged to share content online is contrary to that interest."

• The Public Interest Internet — A series from the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Questions? Tips? Comments? wildwestnewsletter@gmail.com