NEWS: Washington State Will Sue Google Again Over Political Ads

As predicted, Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson is preparing to take Google to court again, accusing the search giant of repeatedly failing to comply with a Washington State law requiring transparency in online political ads.

This will be the second time Ferguson has sued Google over this issue in a little more than two years, and the third time he’s taken legal action against an American tech titan this year.

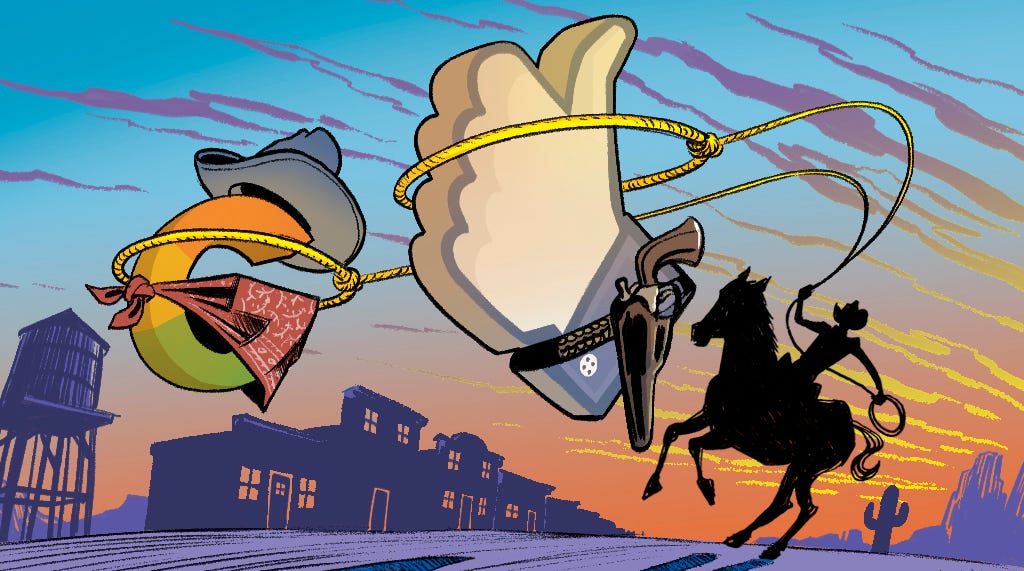

In an era when little is being done to regulate this country’s powerful digital platforms, the actions by Ferguson stand out as a rare instance of government trying to enforce some basic rules for how companies such as Google should interact with democracy.

“I take repeat violations of our campaign finance laws seriously,” Ferguson said in a statement today, in which he made clear that his office, once again, “will file a lawsuit against Google for violating Washington campaign finance disclosure laws.”

The new move comes as Ferguson is already in the midst of prosecuting Washington State vs. Facebook, a case that arose out of a similar pattern of alleged lawbreaking by a global tech giant.

In August, a Seattle judge rejected Facebook’s attempt to have that case dismissed, setting up an ongoing courthouse clash between Washington state’s right to regulate its own elections and Facebook’s claim that Washington state has adopted “exceedingly burdensome" disclosure requirements that should be struck down because, among other things, they allegedly violate the First Amendment.

Based on past statements from its lawyers, Google seems likely take a similar legal approach should it choose to fight Ferguson in court.

There’s another possible outcome, though. A third and broadly similar case, Washington State vs. Twitter, was filed last week by Ferguson and immediately closed with an admission of guilt by Twitter and an agreement by the company to pay $100,000 to Washington State’s “Public Disclosure Transparency Account.” In ending that case, Twitter said it was expressing its “commitment to transparency and accountability.”

At the time, a Twitter spokesperson also noted the influential social media platform no longer sells political ads because of “our belief that the reach of political speech should be earned and not bought.”

By today announcing only his intent to file a new lawsuit against Google—rather than actually filing the lawsuit—Ferguson is meeting a statutory obligation. He had to make his plans clear one way or another before this day was out. But the move also ends up giving everyone involved a bit more breathing room.

Ferguson’s office gains extra time to prepare its lawsuit while Google gets additional time to consider whether it wants to head down the path of litigation, like Facebook; down the path of a quick guilty plea and financial penalty, like Twitter; or perhaps down some other unique path of its own.

Whatever the outcome, the allegations in Washington State vs. Google are set to center on the sort of repetitive law-breaking that was flagged as a concern in the recent US House of Representatives report on how Facebook, Apple, Amazon, and Google engage in monopolistic practices and skirt government oversight.

“Courts and enforcers,” the House report said, “have found the dominant platforms to engage in recidivism, repeatedly violating laws and court orders. This pattern of behavior raises questions about whether these firms view themselves as above the law, or whether they simply treat lawbreaking as a cost of business.”

Like Facebook, Google banned political ads targeting Washington state back in 2018, in an effort to avoid this state’s uniquely tough disclosure laws. Google’s prohibition was rolled out first, on June 7, 2018. Facebook’s ban came more than six months later.

At the time, both Facebook and Google were facing lawsuits from Ferguson due to years of alleged failure to comply with Washington state’s unique disclosure rules. Those rules require companies that sell political ads aimed at Washington’s statewide and local elections to maintain, and make public “upon request,” a significant amount of detail on each ad’s financing, appearance, and reach.

In December 2018, Ferguson’s lawsuits were settled when Google and Facebook agreed to pay $200,000 each. Like the recent Twitter payment, that money went into the State of Washington’s “Public Disclosure Transparency Account.” But unlike the recent Twitter case, Facebook and Google were allowed to avoid any admission of guilt in 2018.

At the time, Ferguson offered a warning. He said the companies had better follow the law going forward, or “they’re going to hear from us again.”

Almost immediately, both Facebook and Google began flouting the law again.

As Wild West noted in a recent newsletter, Facebook continues to sell political ads in Washington state to this day, despite its ongoing ban on such ads, and the company is now fighting its second Ferguson lawsuit for allegedly refusing to disclose information about its Washington state political ads.

The situation with Google appears to be pretty much the same. An analysis of public data by Wild West shows that over the more than two years since Google’s Washington state ad ban went into effect, the company has sold around $200,000 worth of political ads to more than 50 different campaigns and political committees in Washington state, targeting races for everything from state legislature to city council.

Google’s sales of political ads have continued into the current election season, with several 2020 candidates and committees reporting Google ad buys this month, just a few weeks out from the third November Election Day to pass since Google’s ad ban first went into effect.

Asked about these ongoing ad sales and Attorney General Ferguson’s looming lawsuit, a Google spokesperson said: “We don’t accept Washington state election ads. Advertisers that submit these ads are violating our policies and we take measures to block such ads and remove violating ads when we find them. We have been working cooperatively with the Washington Public Disclosure Commission on these issues and look forward to resolving this matter with AG Ferguson’s office.”

The new case Ferguson is preparing against Google arises from two citizen complaints that have, over the course of more than a year, wound their way through the Washington State Public Disclosure Commission and then onward to the more powerful AG’s office.

One of those complaints was filed by me. In March of 2019, nine months after Google’s ad ban went into effect, I asked Google for details on ads that had recently been purchased to influence a ballot measure fight in Spokane. The ballot measure at issue was pretty standard, asking voters to approve a plan to raise local property taxes in order to fund increased police and fire services.

But for this off-season election, a campaign called “Yes for Public Safety” had been able to buy thousands of dollars in supposedly banned Google ads. Here’s one of those ads:

Nothing outrageous, but I wanted to know more about the money behind the ads and their reach. To this day, however, Google has not provided me with the details, as required by law. Instead, investigators with the Public Disclosure Commission were able to learn from Google that the “Yes for Public Safety” campaign paid Google $4,665.85 for the ads, which were shown 6.2 million times on targeted screens in the Spokane area during the lead-up to voting.

The “Yes for Public Safety” campaign won, and it’s important to note that the measure it was backing probably would have passed even without these Google ads. But it’s also worth noting that there are only 210,000 people living in Spokane. Only about 40,000 people ended up voting in that particular February election. Yet this small, relatively low-stakes election was quietly barraged with 6.2 million targeted displays of Google ads.

Now imagine a tighter race in an equally small town—or even a big city—that’s being quietly targeted by Google ads that flash millions of times on certain local screens, but are invisible to anyone who’s not targeted. One can see the obvious value in the public being able to know more, in real time, about what’s going on.

The other complaint against Google was filed by Tallman Trask, the University of Washington law student and activist who’s also responsible for the complaint that led to last week’s Twitter settlement.

In October 2019, Trask asked Google for information on a specific set of ad purchases that were targeting Seattle’s tense city council elections. In addition, Trask made a much broader request. He asked Google to provide legally required disclosures on “any political ads related to 2019 elections in Washington state.”

The Public Disclosure Commission referred both cases to the AG’s office on September 3, and today’s announcement by Ferguson indicates that after reviewing the cases, he believes Google has, once again, broken state campaign finance law.

He noted that the law in question traces to a 1972 citizens initiative passed overwhelmingly by the people of Washington state. That initiative mandated transparency in elections, and Ferguson promised: “We will continue working to ensure that our elections are transparent.”

As always, a few of the stories I’ve been tracking this week:

• “The case has unlocked the full power of existing law” — Ellen Weintraub, of the Federal Election Commission, on how Justice Brett Kavanaugh may have inadvertently made it easier to combat foreign interference in US elections.

• “The Citizen Browser Project” — A very interesting effort by The Markup to learn more about the secret algorithms that power American social media.

• “We’re drowning in lies” — Emily Bazelon, exploring the origins and limitations of a particular view of free speech that, in the digital era, has helped to enable “mass distortion of truth.”

• “Propaganda” — The New York Times on “a fast-growing network of nearly 1,300 websites” that masquerade as local news but are really conservative-funded, “pay-for-play” operations capitalizing on the die-off of local news.

• “Clarence Thomas’ surprise” — Judd Legum on a notable statement from the conservative Supreme Court justice regarding the tech giants’ favorite liability shield.

• “Twitter and Facebook were right” — The Washington Post editorial page on the companies’ recent efforts to slow the spread of a sketchy, Giuliani-connected New York Post article that seems likely to have been part of a misinformation campaign targeting Joe Biden.

Questions? Comments? Tips? Write to me at: wildwestnewsletter@gmail.com